A coup is a coup is a coup. In the past, you needed the military; now it takes a roomful of billionaires and social media.

I’m so aghast at what has just happened in America. More than once I’ve thought all the democracies in the world should have a vote in their elections, since the United States colonizes the Zeitgeist, never mind global economies. I join the armada of journalists and writers warning against the coming suppression of free speech, and there’s no better example than Elon Musk attacking the whistleblower Alexander Vindman right now.

I teach theatre to undergraduates and on the Day After, I faced 32 haggard, tear-stained faces, all of them waiting for me to show the way. I felt as shattered as they did. However, I’ve studied the lives of the shattered, of refugees and prisoners-of-war, and the one thing I’ve learned is to look up. So I told my students that in times of crisis, theatre could give them three sources of resilience.

One was the motto engraved on our hearts: The Show Must Go On.

Two was the fact that theatre depends on a community. There is no theatre without an audience, and no solo show that doesn’t depend on at least one other person — the stage manager, or the person at the box office. Theatre is tribal.

Three was the ability to improvise.

I told them these three things, and then I made them sing Row row row your boat…Life is but a dream in canon. We all cheered up.

In times of crisis, I have a Thing Four that I depend on, namely books. Coincidentally, my latest five all fed in to what I needed right now. Maybe they will fortify you, too, my bookish friends, against what’s coming.

#71 in 2024

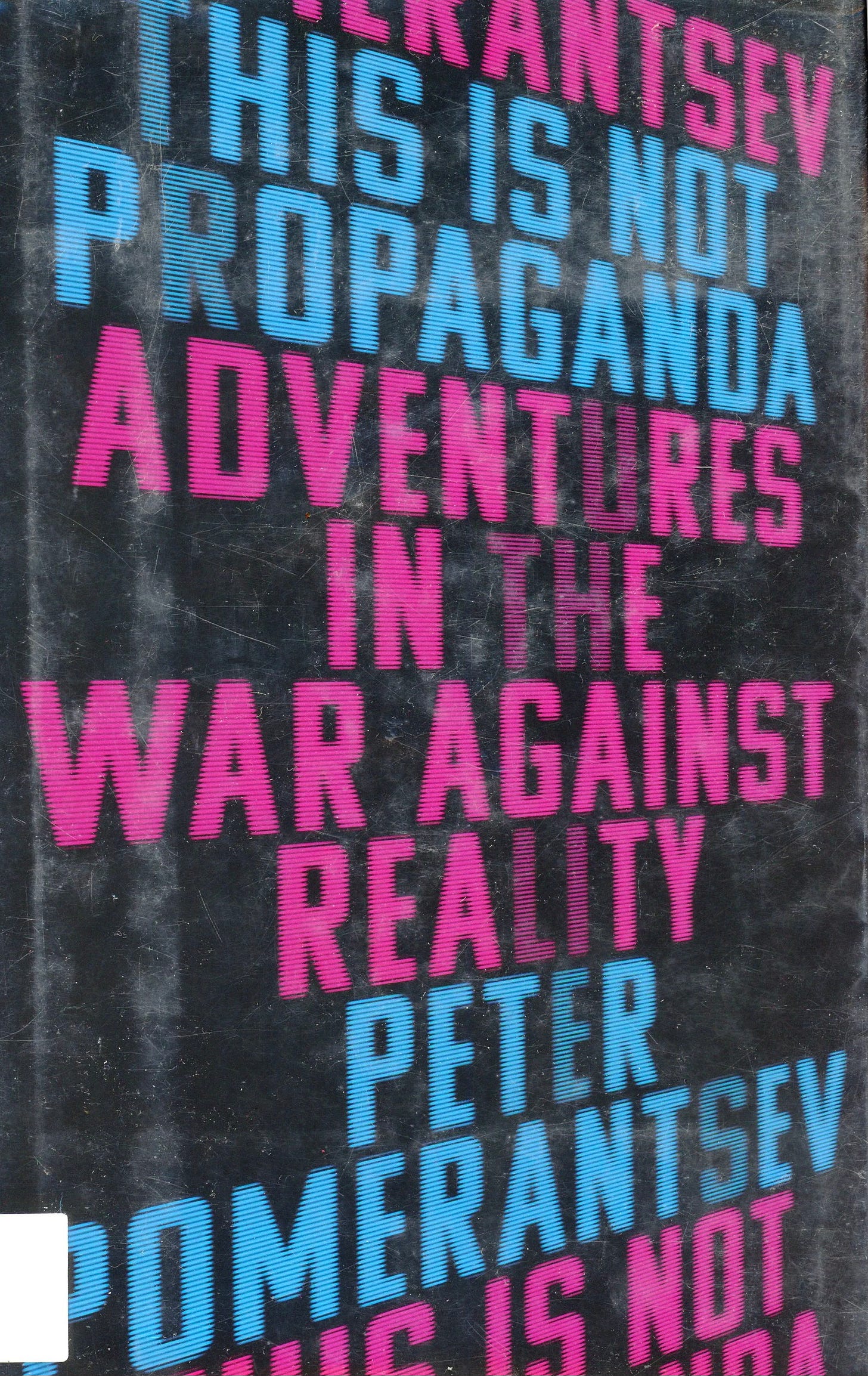

Peter Pomerantsev’s This is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality was a hit-the-nail-on-the-head book I happened to be reading on the day the votes came in. He chronicles the relentless assault on truth in countries as varied as the Philippines, Mexico, Yugoslavia, Estonia, England, Ukraine, Italy, China, highlighting the journalists and activists who are resisting in whatever way they can, including with pranks and ‘laughitivism’. A Russian manual from 2011 called Information-Pyschological War Operations: A Short Operation and Reference Guide describes how the deployment of information weapons works like an invisible radiation. “The population doesn't even feel it is being acted upon. So, the state doesn't switch on its self-defense mechanisms."

Pomerantsev was born in Ukraine in the late 1970s, where his father was detained by the KGB for sharing books by Solzhenitsyn and Nabokov. His parents were among the few allowed to emigrate on a Jewish visa and moved to England when he was four years old. He blends reportage with family history to explore how to reimagine our politics at a time when reality is disappearing.

How can you fight an online mob? You couldn't even tell how many of them were real.

The book was published in 2020; it must be getting more au courant every day. Tune into a Ted Talk where Pomerantsev admits that it’s easy to despair. But before we surrender… He suggests ways to fight disinformation successfully, which include, by the way, pornography.

For those of you with Baltic interests, there’s a great section on Estonia and a citation of a study by Jānis Bērziņš of the Latvian Military Academy.

#72 in 2024

Poet Derek Walcott reached out his posthumous hand to me in The Arkansas Testament. The collection is split into ‘Here’ and ‘Elswehere’ and it’s the second part that I clung to. Even his poem to the long-suffering, standing-in-line-at-the-prison poet Marina Tsvetaeva seemed portentous.

As soon as its noise rattles off, / the surf, or a frenzy of palms, / hisses, “You had losses. Enough, / You can’t hold them all in your arms.”

The poem which gives the book its title was written in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where Walcott stays in a $17.50 motel.

STAY BLACK AND INVISIBLE

TO THE SIRENS OF ARKANSAS

There are things that my craft cannot wield, and one is power.

#73 in 2024

A friend of mine spent an entire year reading mystery novels as a way of sheltering from grief. I bet they read everything by Josephine Tey. That name is the pseudonym for a Scottish writer called Elizabeth MacKintosh who used ‘Josephine Tey’ for the first time to publish A Shilling for Candles in 1936. Maybe she thought her real name was boring. Maybe she was inspired by stage names. She’d just had a show produced in London’s West End and I bet she wanted to kill some of the actors. The plot involves a dead movie star, a plucky teenager, a charming Inspector Grant and a school of red herrings.

“No,” agreed the ambulance man. “The butler is probably telephoning the station now in great agitation.”

Alfred Hitchcock made a forgettable film version called Young and Innocent with an actress called Nova Pilbeam. Who makes these names up? Can I buy one at the Name Factory?

He left his Sunday kidney and bacon untouched .

#74 in 2024

Oh boy, Luisa Lim, you showed up just in time. I didn’t think I would like Indelible city : dispossession and defiance in Hong Kong and yet it felt like the perfect stiff drink to down after the election.

Hong Kong is a city that was always colonized and fought for its rights, harder and harder, and lost again and again, and is still losing. And yet Lim and the city still fights. The book starts with a dedication to all those who really fucking love Hong Kong. The spirit of resistance is captured by a character the city loves, called The King of Kowloon, an indomitable, eccentric, nuts-o graffiti artist, whose spirit cannot be erased.

Lim is an expat Hong Konger and award-winning journalist, who acknowledges her status as a mixed-blood, Eurasian, half-caste, half-Chinese barbarian. As she relates the story of Hong Kong, she struggles against the duty of objectivity, because the stakes are so very high. Many of the people she interviewed have since been sentenced to jail.

This gripping story of the unraveling of one of the world’s greatest cities is based on an archive containing dozens of interviews conducted in the 1980s and 90s by HK political scientist Steve Tang, including three British governors and six key advisers. The words they use to describe the Chinese takeover of the colony are dismayed, angry, upset, scared, devastated.

It was hard to function with a perpetual sense of anger, yet the muting of emotion that accompanied the normalization of the abnormal was alarming.

Sound familiar?

We were all living in the eternal present, where the future was so uncertain that it was unseeable, and the past had receded into irrelevance.

The other night I finished teaching my course in directing theatre and as everyone packed up, I mentioned to a student from Hong Kong that I’d just finished a book about their home town. “Oh,” they said. “Was it…political?” I hesitated, in case my reply would cause them trouble, and then said yes. Relief flooded their face. They’d barely spoken to me all term, but now they had a lot to say. About how unreal the world seemed to them sometimes, sitting next to people talking about the shows they were in while a message on their phone said that a friend in Hong Kong had just been arrested.

#75 in 2024

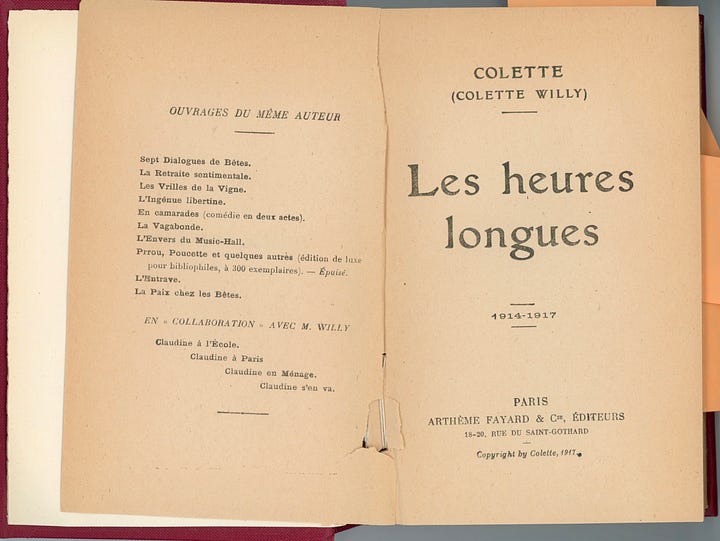

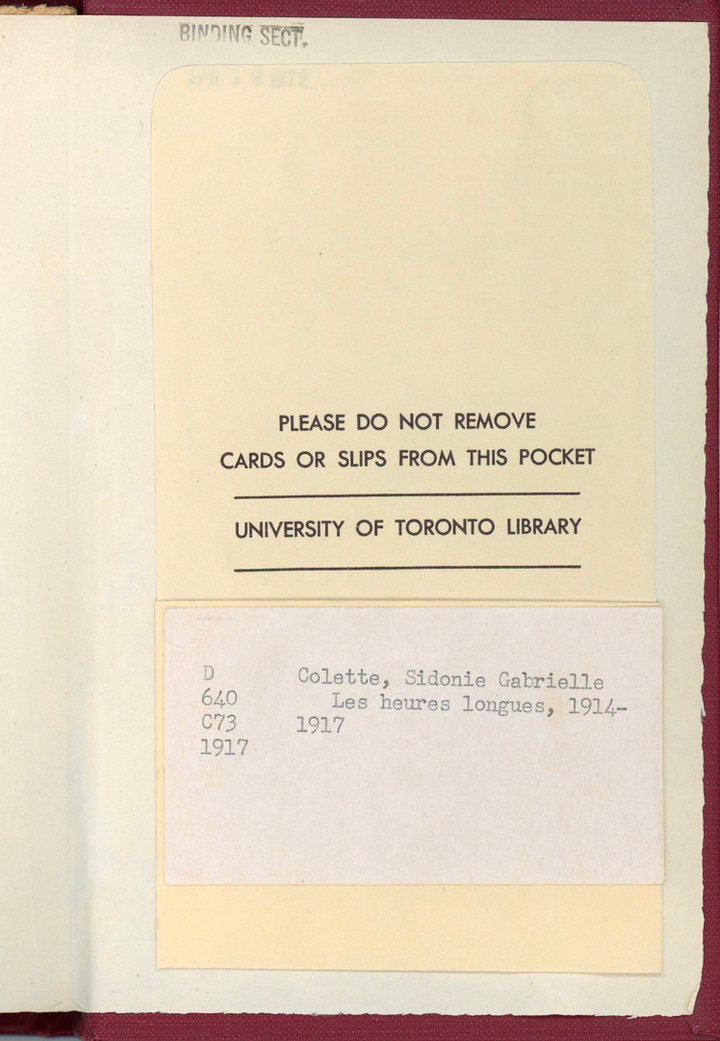

I don’t know why Les Heures Longues by Colette hasn’t been translated. I decided to tackle it in French (thank you Google Translate) and that led me to the original publication of these wartime impressions published in 1917. There’s always a special pleasure in holding something very old in your hands; in noticing that her surname on the title page is still linked to her ex-husband (Colette Willy); that her full name is on the card pocket at the back.

Colette starts writing brief snapshots in 1914, when the war arrives just like a Trump win, with a sense of unreality. The very first sentence is La guerre? …Jusqu’à fin du mois dernier, ce n’était qu’on mot énorme…La guerre? Peut-être, oui, très loin, de l’autre côté de la terre, mais pas ici.

The war?…Until the end of the previous month, it was just a gigantic word…The war? Maybe, yes, far away, on the other side of the world, but not here.

The journal consists of brilliant glimpses into the shifting moods of the population, the bravery of the first wounded, the anguish caused by the absence of able-bodied men, when women live with dread and the children have to stack the hay. Colette spends several months in Italy, appalled by the attacks on Venice, probing her own growing nationalism. After a year, as the war drags on, the entries drop off. Perhaps the saddest one is how she realizes that her four-year-old daughter is a child of war, knows nothing but war. The battles have not yet ended when Colette stops writing about them.

What will the child be like who grows up under the dictatorship of three South African billionaires and the American far right?

*

Some happy news: my friend Martha Baillie won the Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Nonfiction (which is $75,000), for her memoir There is No Blue, one of my top ten books of 2023, which I wrote about here.

I am back to riding the Toronto subway where based on a daily subjective survey I can report that less people read actual books. But I still have some photos to share from the London Tube. All glory to ye real book-readers.

Currently reading: Jean Giono, Fragments of a Paradise, translated from the French by Paul Eprile, first published 1948

The New List:

Featured Author: Colette, Les Heures Longues, 1917 (see above)

Second Latest Title Saved: J. M. G. Le Clézio, Desert, 1980 (French Nobel Prize winner mentioned by Lauren Groff)

Reader Recommended: Judith Thurman, Secrets of the flesh: a life of Colette, 1999 (two bookish friends named Paul insisted that I should read this sooner not later)

Oldest Title on the List:

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem : a report on the banality of evil, 1963 (this expert on totalitarianism is, sadly, en vogue)

The Random Six:

William Maxwell, The Chateau, 1961 (novel set in post-war France)

Josephine Tey, A Shilling for Candles, 2002 (see above)

Delta Willis, The sand dollar and the slide rule : drawing blueprints from nature, 1995 (non-fiction)

George Orwell, Books v. cigarettes, 1946 (essays, can’t wait)

Will Arbery, Heroes of the Fourth Turning, 2020 (an American play I saw last year)

Luisa Lim, Indelible city : dispossession and defiance in Hong Kong, 2022 (see above)

If you’re wondering how my list is put together, check out my system here.

Also, here are more people reading actual books on the Tube in London.

Hi Banuta, thank you for previous recommendations, Timothy Morton’s “ Hell “ and Cole Nowicki’s “Laser Quit Smoking Massage”. Totally different and enjoyable in their totally different ways. Fun to pick one up after the other for a change of pace! Best, Barbara G