#46 in 2024

Nasty, brutish, and short is the life of a Rickshaw Boy in Beiping [sic], China, in the 1930s. Lao She tells the story of Xiangzi, a boy so strong that he could blow a hole in the ground just by farting. Sadly, trouble lurks ahead, in the shape of marauding soldiers, bullying women, or political machinations which the boy doesn’t understand. The author loves Beiping, but his near-clinical description of the hopelessness of the downtrodden is crushing. Also, the climate isn’t great.

No place escaped the dry, blistering heat or oppressive air that turned the ancient city into a blazing kiln. People could hardly breathe; dogs sprawled on the ground, pink tongues lolling from their mouths…the streets were deathly quiet.

The world was a like a fiery mirror on which every ray of sunlight seemed focused, turning everything it touched into flame. In that engulfing whiteness, every color hurt the eye, every sound grated on the ear, and every smell carried with it a stench from the steamy ground.

The translator Hugo Greenblatt warns against other translations which have gone so far as to change the ending of the novel.

#47 in 2024

We walk into one another’s lives, we change them and are changed deeply and forever, we part ways. Each time a part of our hearts seems to shrivel and die, it doesn’t.

The rickshaw boy wore me out. I turned to the book Walking with Abel: Journeys with the Nomads of the African Savannah for respite. I knew my writer friend Anna Badkhen was impressive, but now I was cowed. Because, boy, are there a lot of cows in the savannah; cows and sky and rumination. I chewed on the unfamiliar word ‘transhumance’.

The cows set out with an incredible lowing. Hooves clinked on plutonic rock like hail. Hooves sucked into sand. Flanks, swished against dry reeds, against the hot and dusty hides of other cows.

In 2013, Bakdhen beds down for an entire year with a Fulani family in central Mali, living with a patriarch who is wise, yet cannot read, and whose wife, Fanta, can pick up a stone with her toes while balancing a full calabash of water on her head. There is war nearby, and the young men study al-Qaeda executions on their phones, but Badkhen, a former war correspondent, refuses to highlight violence. Like me, she is thirsting for a different perspective on life.

To enter such a culture. Not an imperiled life or a life enchanted but an altogether different method to life’s meaning, a divergent sense of the world. To tap into a slower knowledge…

*

“Is there a land without death, Anna Bâ?” she said. “We are used to leaving everything.”

To spend a lifetime walking way. To bid farewell over and over, all the time. To anchor your heart to the next campsite and then move on. To have your heart broken and reset like a bone.

*

I made my bed in the mud from a sheet of blue tarpaulin. Fits and starts of frog song. The rapping of a goat’s ears. Thunder somewhere. Quietude of the soul.

#48 in 2024

“It’s a perfect summer read,” said my bookish friend Maureen, “it's absolutely hilarious.” Enter R. F. Kuang's Yellowface.

Bestselling Asian author Athena Liu chokes on a pancake and dies at the feet of her less successful friend June. Poking around in her after-effects, white-skinned June finds the draft of Athena's latest book and rewrites it from one end to the other, then publishes it under her own name. The book is a massive success. The subject is a slice of Chinese history during World War I. Is June a thief? How much? Was she allowed to write about China? What about the late Athena? She turned her friends’ intimate confessions into literary artifacts. Was that theft, too? And what should June do when her friend's ghost shows up?

“Who has the right to write about suffering?”

Kuang turns hardline issues topsy-turvy like a kid that's sick of all the rules, making mischief. She's appropriating as well -- writing from the perspective of a white woman, though she herself is Asian. Screw you, cancel culture! The book punctures the hypocrisies of the publishing world, and Kuang make sport of the ambitious young writers who aim to make shitloads of money, be the next Stephen King, products of Yale and prestigious workshops, governed by their Twitter and Instagram accounts. Go ahead, laugh. Bring the sunscreen.

To stop writing would kill me. I’d never be able to walk through a bookstore without fingering the spines with longing, wondering at the lengthy editorial process that got these titles on shelves and reminiscing about my own. And I’d spend the rest of life curdling with jealousy every time someone like Emmy Cho gets a book deal, every time I learn that some young up-and-comer is living the life I should be living.

#49 in 2024

Colette, Mitsou, and Music-Hall Sidelights, 1919 and 1913

Say you’re poor and alone and female in Paris and you’d like to avoid working as a prostitute, then you could perform in a revue in Montmartre wearing nothing but a red and black froth of tulle. You find a Respectable Man, who supplies an apartment and a maid in exchange for lunchtime favours. One day you hide a couple of soldiers who are late for curfew in your dressing room. The lieutenant in blue is especially dashing, and he might die in the trenches any day. The letters you write each other are so romantic— but then, alas, you go to dinner.

Mitsou is a novella that is nearly a play, paired with pre-war vignettes collected from Colette’s life in the theatre, an anthology called Music-Hall Sidelights. Other translators choose Backstage at the Music-Hall as a title, which seems better to me. Maybe it’s time for a new translation? This version is from 1957 and the translator ir Raymond Postgate.

No, don’t kiss my hands, not even in a letter. They’re not nice enough; the liquid white ruins the skin and besides I’ve put too much varnish on the nails. But kiss the crook of my arm; it has a lot of tiny rivers in blue and green and when you kiss it you need only be thinking of the army maps.

Colette’s snapshots of backstage are like a program you want to save: characters like Beautey, the eighty-year old actor; the girl friend called Bit-of-Fluff; La Roussalka aka “Poison Ivy” who claims her fatherrrr controls rain and sunshine in Moscow. The dressing rooms stock iced absinthe and jars of rouge and Leichner eyebrow pencils. The midget pony, the tiny brown bear, and the lady with the detective dogs stumble up the winding stairs; they sweat alongside all the penniless girls and boys in front of the blinding footlights, working hard, shunning thought, and refusing to be burdened with regrets, remorse or memories

This Colette has the soul of a theatre-addict now. I’m in love with her again.

#50 in 2024

My people, you were really something fucking fine/on the morning of first arrests

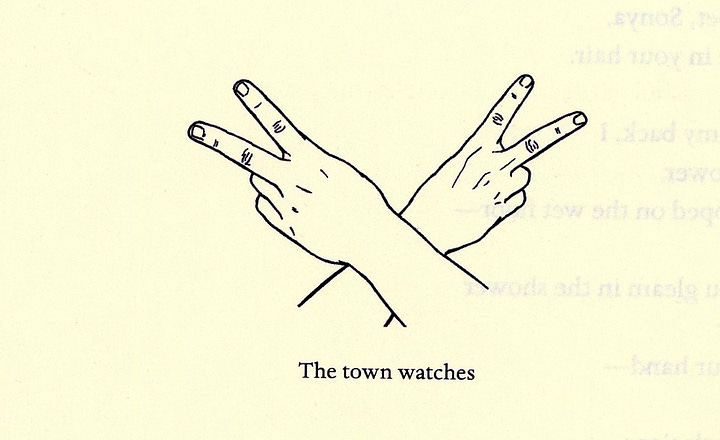

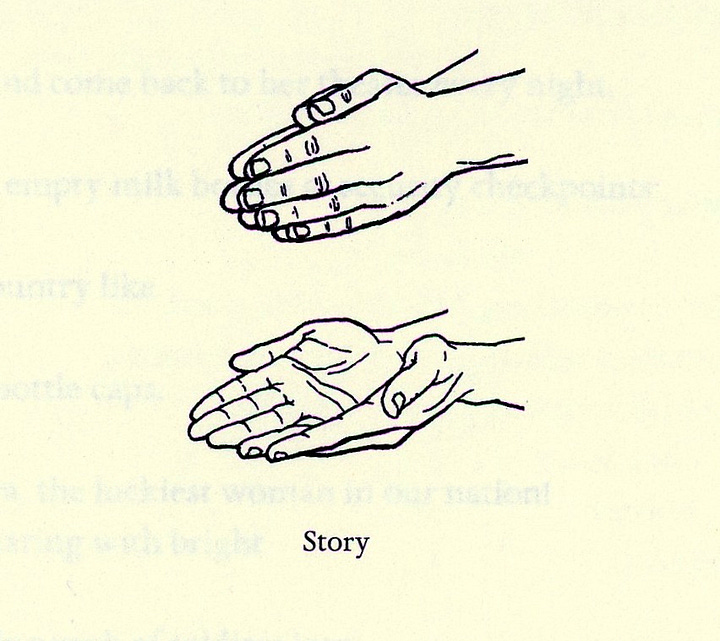

Speaking of how to write about violence, my bookish friend Anna (friend of bovines, the same) recommended Ilya Kaminsky’s book Deaf Republic. The only thing wrong with this book is its ugly cover. Graywolf Press usually does better.

Kaminsky tells the story of what happens when a deaf boy is killed by an occupying army. In retaliation, the townspeople pretend that they are all deaf. The soldiers are not pacified. Militant puppeteers resist anyways. All I could think about was Ukraine, and then Gaza, and then, and then.

Kaminsky was born in the former Soviet and is now an American citizen, a Jewish-Ukrainian one . In his photos, he is always smiling. Writer Garth Greenwell calls Kaminsky the most brilliant poet of his generation, ‘one of the world’s few geniuses’.

**

Skipped these books —

Too Many Words: Marianne Wiggins, Properties of Thirst

When the far right is in the ascendant, life is too short to read Five of the Best Soviet Plays of the 1970s

I’m a big fan, but not that big: Congenial Spirits: the selected letters of Virginia Woolf

Dreadful translation: Novalis, Hymns to the Night

Currently reading: Amia Srinivasan, The right to sex : feminism in the twenty-first century, 2021

**

The New List (coincidentally, contains lots of China)

Featured Author: Colette, Mitsou, and Music-Hall Sidelights, 1919 and 1913 (see above)

Second Latest Title Saved: Amia Srinivasan, The right to sex : feminism in the twenty-first century, 2021 (see above)

Reader Recommended: Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic, 2019 (see above)

Oldest Title on the List: Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, 2003 (I may have read this already)

The Random List:

Stephen R. Platt, Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the epic story of the Taiping Civil War, 2012 (China in the 1850s)

Donna Jeanne Haraway, Manifestly Haraway: the cyborg manifesto, 2016 (1980s classic discussion of human/machine/animal boundaries)

Ji Xianlin, The Cowshed: memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, 2016 (a 1998 bestseller in China)

Charles Yu, How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, 2010 ( a novel, know nothing)

Garth Greenwell, Mitko, 2011 (queer novel, written before Cleanness, loves Kaminsky)

Dawnie Walton, The final revival of Opal & Nev: a novel, 2021 (know nothing)

If you’re wondering how my list is put together, check out my system here

Bonus book:

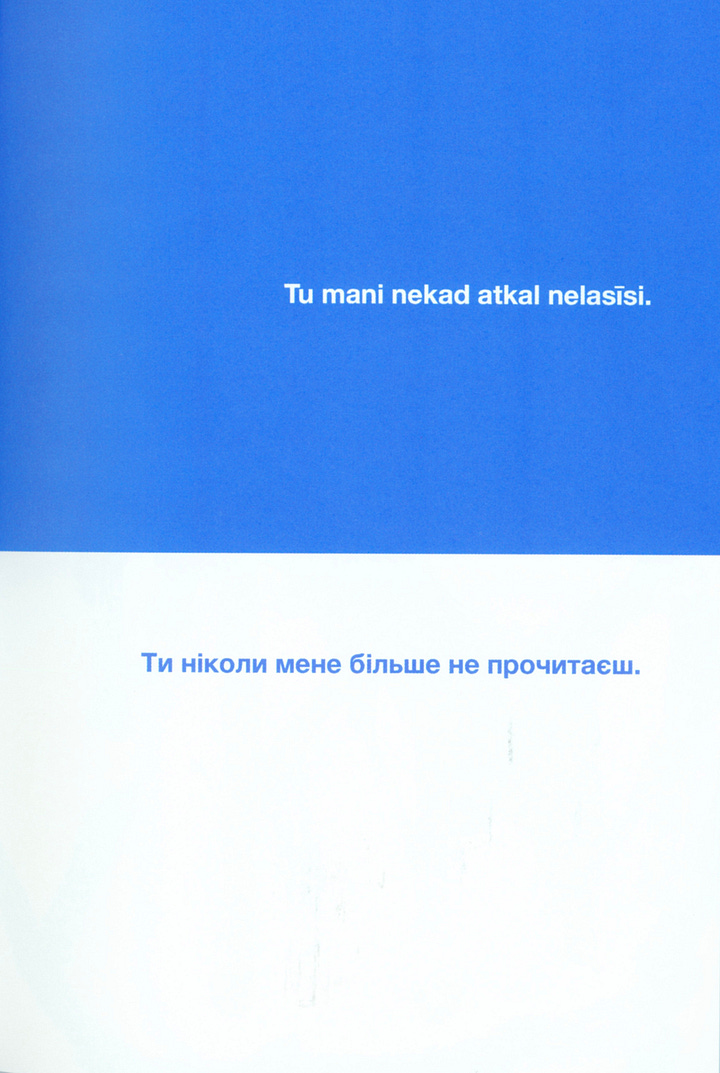

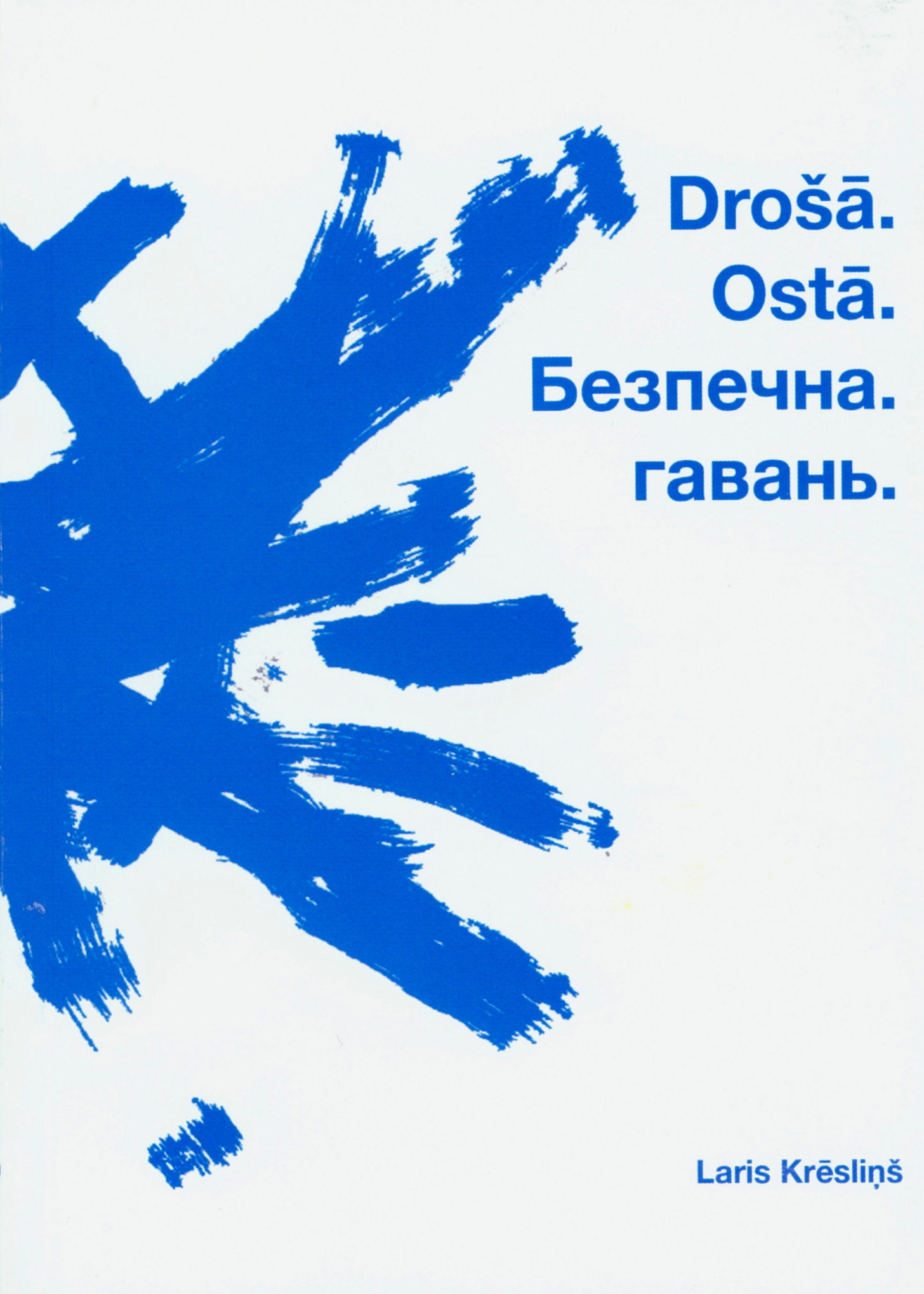

The Philadelphian poet, performer, and music magazine publisher Laris Krēsliņš gave me a small book of poetry in Latvian and Ukrainian that is a delight to handle, especially if you are, like me, bewitched by the colour blue. The title is Drošā. Ostā. — Safe. Harbour. The poems are as short and thin as band-aids. Call them koans. You can buy the book here. All proceeds from sales go to Spilka, ‘an independent collective of art, service and cultural workers dedicated to providing people in Ukraine with lifesaving resources and critical supplies in the face of the ongoing Russian invasion and war.”

English translations of the poems are available online.

THe choice of excerpts, the wit and wisdom of your observations, the range of books, the delight in misbehaving authors. Calling Colette the 'boss of sex scenes'. All so excellent! Thank you for your wonderful curating.