None of the books discussed below have anything to do with Greenland and this is not a political blog but I’ve got a platform and I'm using it.

That said, bookish friends, here’s a Fun Fact, coming to you via Book #21: Charlie Chaplin was hounded by the House on Un-American Activities in the 1950s, and while on a transatlantic voyage his permit to re-enter the United States was rescinded. He was a British citizen and he decided never to return to the States. He wrote that whether I re-entered that unhappy country or not was of little consequence to me. I would like to have told them that the sooner I was rid of that hate-beleagured atmosphere the better, that I was fed up with America’s insults and moral pomposity.

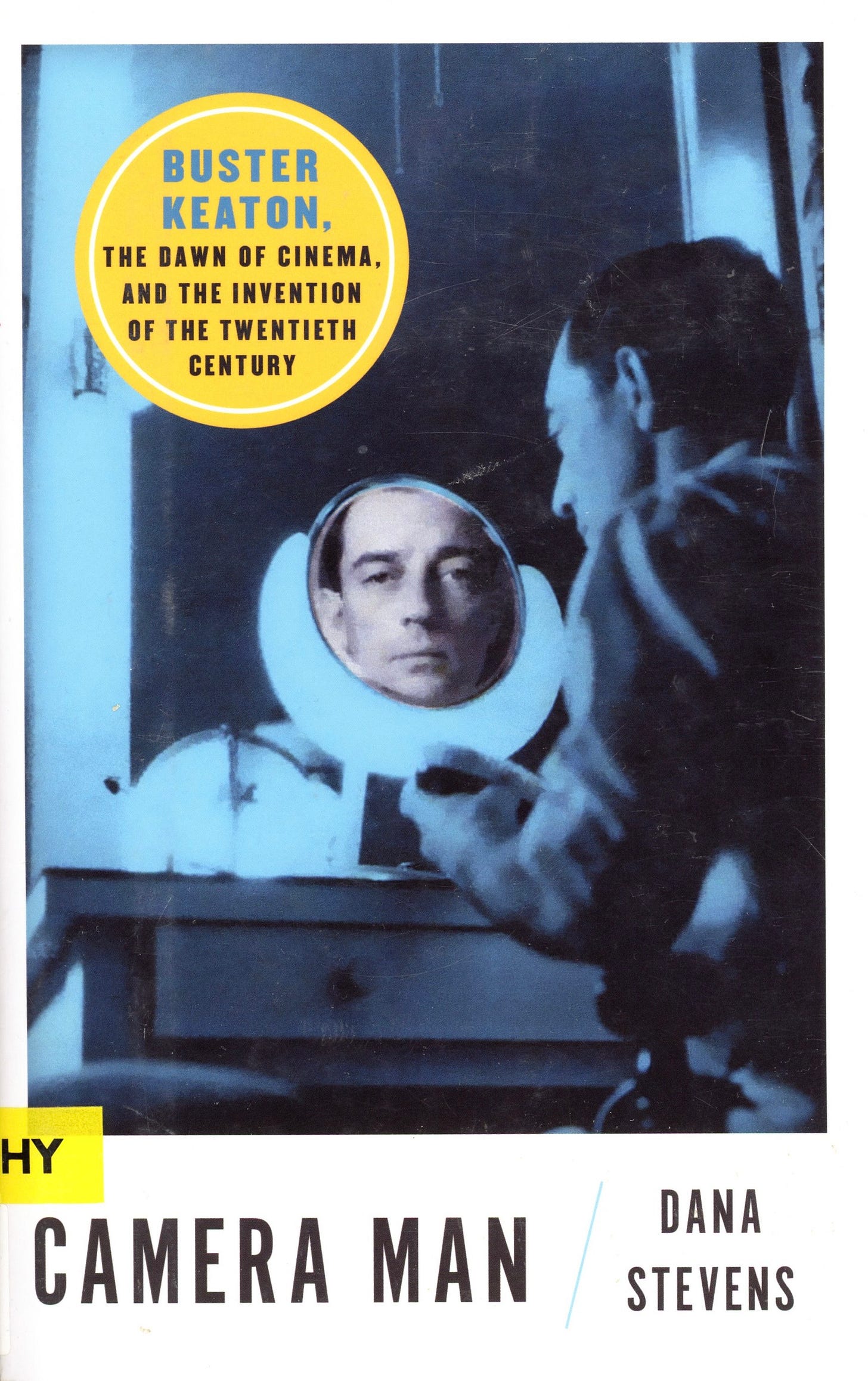

#21 in 2025

“If ever we want to punish our very unborn offspring severely,” his review began, “we shall tell him, or her — or them, that he (she, they) cannot go to see Buster Keaton.”

It turns out that a lot of people have no idea who Buster Keaton is. If they know anything, they know his stunt: the wall of a house falls down on top of him and he is miraculously left standing. The biography by Dana Stevens, Camera man : Buster Keaton, the dawn of cinema, and the invention of the Twentieth Century drives home what an important artist he was. Born in a watershed year, 1895, his life encompasses all the changes of popular performance in the next century, from vaudeville to that new thing called silent films to that other new thing called talkies, to the next new thing called television.

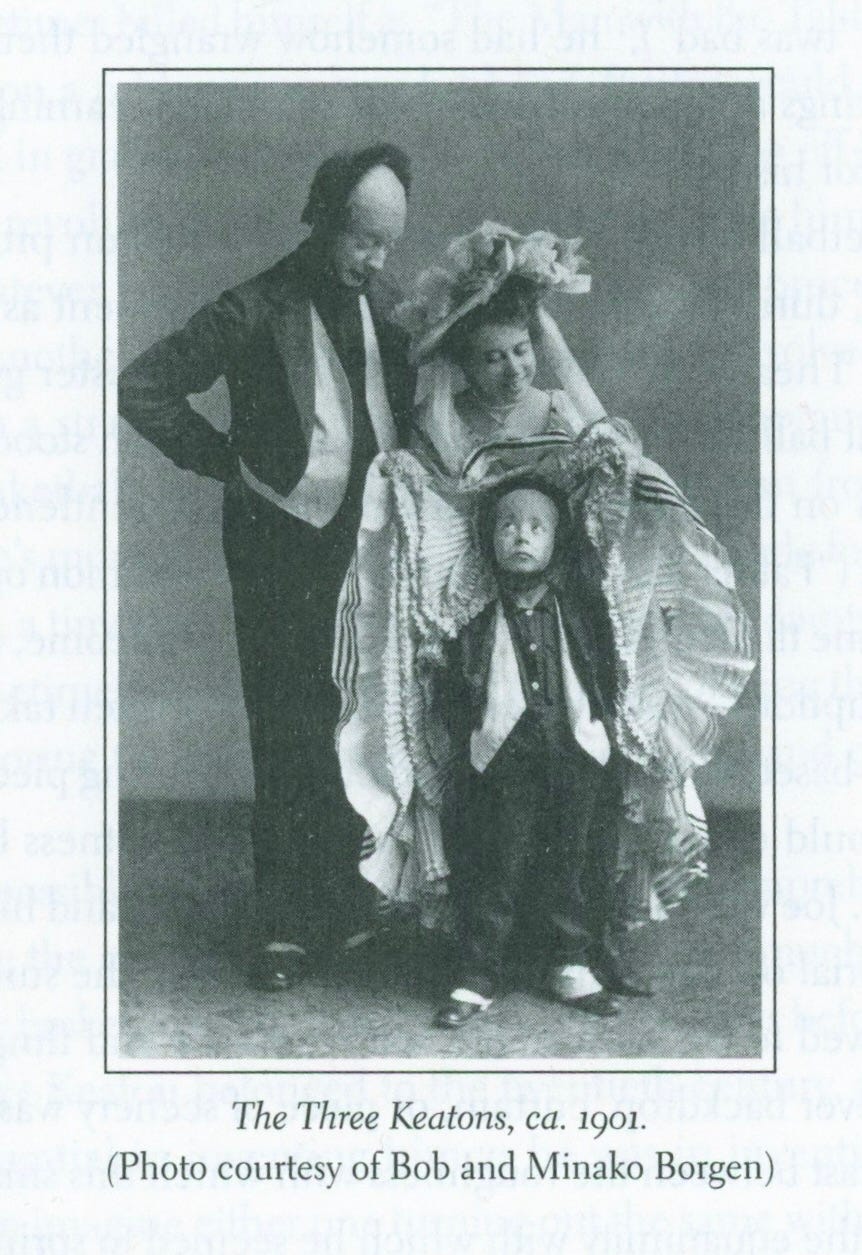

Keaton knew nothing but performance for his whole life. His parents were traveling vaudevillians and his mother sewed a handle on to a costume so that he could be flung across the stage like a suitcase by his violence-prone Dad.

Stevens works as a journalist for Slate and thus the chapters are short and punchy. Her ambition is to track both cultural history and Keaton at the same time, which includes describing things that didn’t happen. For example, there’ s a whole chapter on how women directors disappeared from Hollywood —vanishing from the high places they had occupied and being shunted into the narrow space they would be allotted for the rest of the twentieth century and into our own. Another chapter sums up the history of Alcoholics Anonmyous, because Keaton became a raging alcoholic who never went to AA.

One of the pitfalls of this entertaining biography is that whenever some film is mentioned, you can find it on Youtube, and there you stay for the next twenty minutes or more. You could do worse than lie on the couch laughing at The Playhouse (1921) where Keaton plays all the parts in a vaudeville show. He’s the conductor, the monkey, the dowager, the stage hand, and also, trigger warning, in blackface.

If you’d like to see the stunt where a house falls on him, open the link.

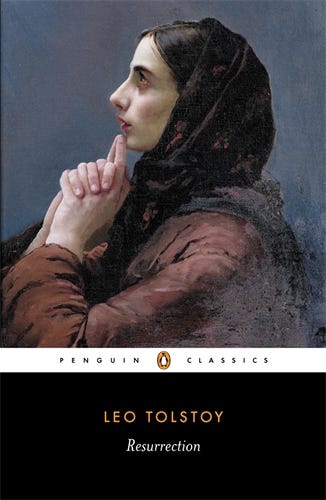

#22 in 2025

So there’s this Russian nobleman who feels bad about owning all this land and subjugating the peasants that work on it (Leo Tolstoy’s self-portrait). One day he's called upon for jury duty. To his horror, he recognizes one of the accused, a prostitute who wasn't a prostitute when he first met her and ruined her life. She is wrongfully sentenced to hard labour and exile. In atonement, he tries to fix this.

Resurrection is Tolstoy’s last book, published in 1899, not long before convulsive revolutions transformed the Russian empire and swept away the Czar. (Translated in 1965 by Rosemary Edmonds.)

Tolstoy was religious and ultimately only Jesus can fix things, which is a bit annoying at the end, but the rest of the novel is engrossing. I was struck by the detail with which Tolstoy described locations like the courtroom, and it occurred to me that he was writing for readers who would never see a courtroom, since there were no photographs and no TV series that made this setting familiar. It’s those details that make him such an irresistible writer as long as you can get past all those patronymics.

He gives you a panorama of Imperial Russia, both the aristocracy and the underworld, the prison system and the church (they excommunicated him for this book). The exiled travel for about three thousand miles by train, by foot, by steamboat, simple criminals, political offenders, the innocent but unfortunate. It isn't all agony; there are hilarious descriptions of officials and underlings and primadonnas and passionate romances. But what really keeps things going is the inner monologue of Tolstoy’s avatar, the nobleman, whose convictions become more and more radical.

…he had conceived a whole-hearted loathing for the society in which he had lived till then; a society where the suffering borne by millions of people in their efforts to ensure the convenience and comfort of a small minority was so carefully concealed that those who benefited neither saw nor could see this suffering and the consequent cruelty and wickedness of their own lives.

… all these people had been arrested, locked up or exiled…merely because they were an obstacle hindering the officials and the rich from enjoying the wealth they were busy amassing from the people.

#23 in 2025

The trouble with Kate Atkinson is that she pulls you in and spits you out. You’ll tear through one book and pant for the next.

It’s good to be reminded how terrifying WWII was for Britain. Transcription is an espionage story that begins shortly before the London Blitz. Juliet is 18 and a good liar and that’s how she gets roped into being a spy, which starts by typing up the recorded conversations of British Nazi sympathizers, the ones next door. Ten years later, the war is over and Juliet is a producer of children’s programs for the BBC. One day she receives an anonymous message. Time to tuck that Mauser back in her handbag.

Atkinson was inspired by a guy who was recruited to monitor the fifth column and posed as a Gestapo Agent, a true story she found in one of the periodic releases of documents from the MI5 to the National Archives. Also, she loves the BBC, even when she pokes fun at it.

You had to ask yourself, which was better — to have sex with any number of interesting (albeit possibly evil) men (and some women too, apparently), to be glamorously decadent, to ingest excessive amounts of drugs and alcohol and die a horrible but heroic death at a relatively young age, or to end up in Schools Broadcasting at the BBC?

Now and then the story gets confusing as the time line jumps around from 1940 to 1981, and since there are so many different characters to follow. Now and then the British love of making jokes about everything starts to feel obnoxious. Nevertheless, it’s a grand mystery with a sucker punch at the end. Excellent commuter fare, and you might miss your stop.

#24 in 2025

She is an unbroken egg; she is a sealed vessel; she has inside her a magic space the entrance to which is shut tight with a plug of membrane; she is a closed system; she does not know how to shiver. She has her knife and she is afraid of nothing.

Reading Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber was like meeting an old friend. Where have you been for so long? Haven’t seen you in ages! Her stories burst upon the scene in 1979 when second wave feminism was cresting and Carter gave an invigorating call to re-think every story you’d ever been told, to cherchez la femme in every narrative and change the story. She turned all the misogynist fairy tales topsy turvy — Bluebeard and the Beast, the wolf and the grandmother. Maidens don't necessarily die, and that monster is actually kind of attractive. The moonlight glittered on his great, hazy head of hair, on the eyes green as agate, on the golden hairs of the great paws that grasped his shoulders so that their claws pierced the sheepskin as he shook him like an angry child shakes a doll. The writing is as ornate as cobwebbed candlesticks dripping wax on a vampire’s coffin, as strange as a robot maid who is the duplicate of her mistress, a simulacra whose bowels churn a menuet.

…what other student at the Conservatoire could boast that her mother had outfaced a junkful of Chinese pirates, nursed a village through a visitation of the plague, shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand and all before she was as old as I?

#25 in 2025

If you believe life is nasty, brutish and short, you will love Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season. Melchor’s poverty-stricken narco-dealing Mexico is made of drugs, unspeakable violence, and so much joyless rutting you could get a rash just reading about it. The Witch is found dead in a small Mexican village, and the story is narrated by a series of characters who are somehow connected to her — from a girl who needed an abortion to the actual murderer.

It must be bad vibes, jinxes causing all that bleakness: decapitated bodies, maimed bodies, rolled-up bagged-up bodies dumped on the roadside or in hastily dug graves on the outskirts of town.

Melchor writes as if possessed; as if the voices of these trapped, hopeless, horrifying people were storming out of her mouth; as if she’s standing in the middle of the highway in a tight leather skirt with her fists planted on her hips shouting at the traffic. She would be nowhere without a comma, without a semi-colon; the sentences are hurled onto the page and boil along like overflowing gutters.

They’re barely old enough to wipe their own asses, these little sluts, and yet off they go, legs akimbo. I‘m going to tell the doctor to scrape you out with no anaesthesia, that‘ll teach you.

Those were the only two things he could think about lately: killing and running away; school was a fucking drag, a waste of time; he was sick of drugs and booze, didn’t get a kick out of that shit anymore; his friends were all a bunch of poor cunts.

…girls all washed up before their time, carried in from some far-flung dump on the same breeze that whipped up the plastic bags, leaving them wrapped around the sugar cane; women tired of life, women who, from one day to the next, would realize that they no longer had it in them to reinvent themselves with every man they met.

Two women whom I love and admire hotly recommended Hurricane Storm as a counterpoint to 2666, as a less pretentious, more truthful witnessing of the same brutality. They are tougher than me. Over the years, I’ve winced my way through a lot of literary violence. I can endure it when its intention is to reveal political injustice. But sometimes the abyss stares back into you. I’d rather be a shackled prisoner on my way to Tolstoy‘s Siberia than sit next to any of Melchor’s characters on a bus.

Translated by Sophie Hughes

Melchor was in her late thirties when she wrote this book; it won the Anna Seghers Prize, a German award for promising young writers; and was on the short list for the Booker Prize in 2020.

*

Currently reading: Oleh Sentsov, Diary of a Hunger Striker & Four and a Half Steps

Wasn’t in the mood for: Nadifa Mohamed, The Orchard of Lost Souls

Daunted by: Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: the definitive history of racist ideas in America

*

Still to go

Ta-da! I have chosen a new Featured Author: Chimamanda Ngoze Adichie, Purple Hibiscus, 2003

Oldest Title on the List: Georges Perec, A Void, 1969 (written without the letter E, bought it used from UK)

The Random List:

Tomasi di Lampedusa, The leopard, 1958 ( a classic)

Malcolm Bradbury, Eating People is Wrong, 1959 (might be funny)

Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: the smartest kid on earth, 2003 (a graphic novel)

If you’re wondering how my list is put together, check out my system here.

My beloved Toronto Public Library is — as they say themselves — a place for creativity and imagination. This is one of their Grand Award Winners in the 2025 Design a Bookmark Contest.

Always impressed by what you plow through and break down with such panache for the rest of us!